It’s not that it doesn’t matter how shopper marketing is organized, it’s that it doesn’t seem to matter. Shopper usually is organized in one of two ways: either as an enterprise-wise, cross-disciplinary initiative that is integrated with sales but is a function of marketing, or as a function of sales and category management.

It’s not that it doesn’t matter how shopper marketing is organized, it’s that it doesn’t seem to matter. Shopper usually is organized in one of two ways: either as an enterprise-wise, cross-disciplinary initiative that is integrated with sales but is a function of marketing, or as a function of sales and category management.

Less frequently, it is set up as a stand-alone function that is connected to sales and marketing but is not positioned as a function of either, per se. Further complicating the picture, our research finds that some organizations are now taking a hybrid approach, in which Shopper is positioned as a function of both marketing and sales.

How Shopper is funded typically determines how it is organized, and how it is funded tends to be governed by whether the organization is more sales- or brand-driven. This is a key point, because priorities sometimes shift, and shopper bounces back and forth between sales and marketing. Its purpose becomes muddy, and consequently its value is questioned. Worse yet, in some organizations, Sales sees Shopper as a source of funding while Marketing sees it as a threat to funding — resenting how much money goes into the cost-of-entry with retailers when they don’t see a direct benefit to their brand.

Hoyt & Company’s “State of Shopper” survey, fielded roughly every two years for more than a decade, found that those organizations fashioned as an enterprise-wide, cross-disciplinary initiative, as a function of marketing, consistently reported better results than those that organized it as a function of sales and category management.

This made sense, because it conformed with the concept of Shopper itself, which is intended to apply the power of the brand at retail to drive growth. Divorcing Shopper from the brand undermines the very concept of Shopper. What’s left is something that is devoid of shopper’s purpose and promise to build brand health and growth by creating brand engagement at retail.

An intriguing dichotomy surfaced two years ago, in our 2016 survey. A solid majority (58.5%) identified Shopper as a corporate, cross-functional strategy, and a significant plurality (48%) viewed Shopper as a function of Marketing, as opposed to Sales (36%) or General Management (16%). However, the way in which Shopper initiatives were being implemented and evaluated told a different story of a “house divided.”

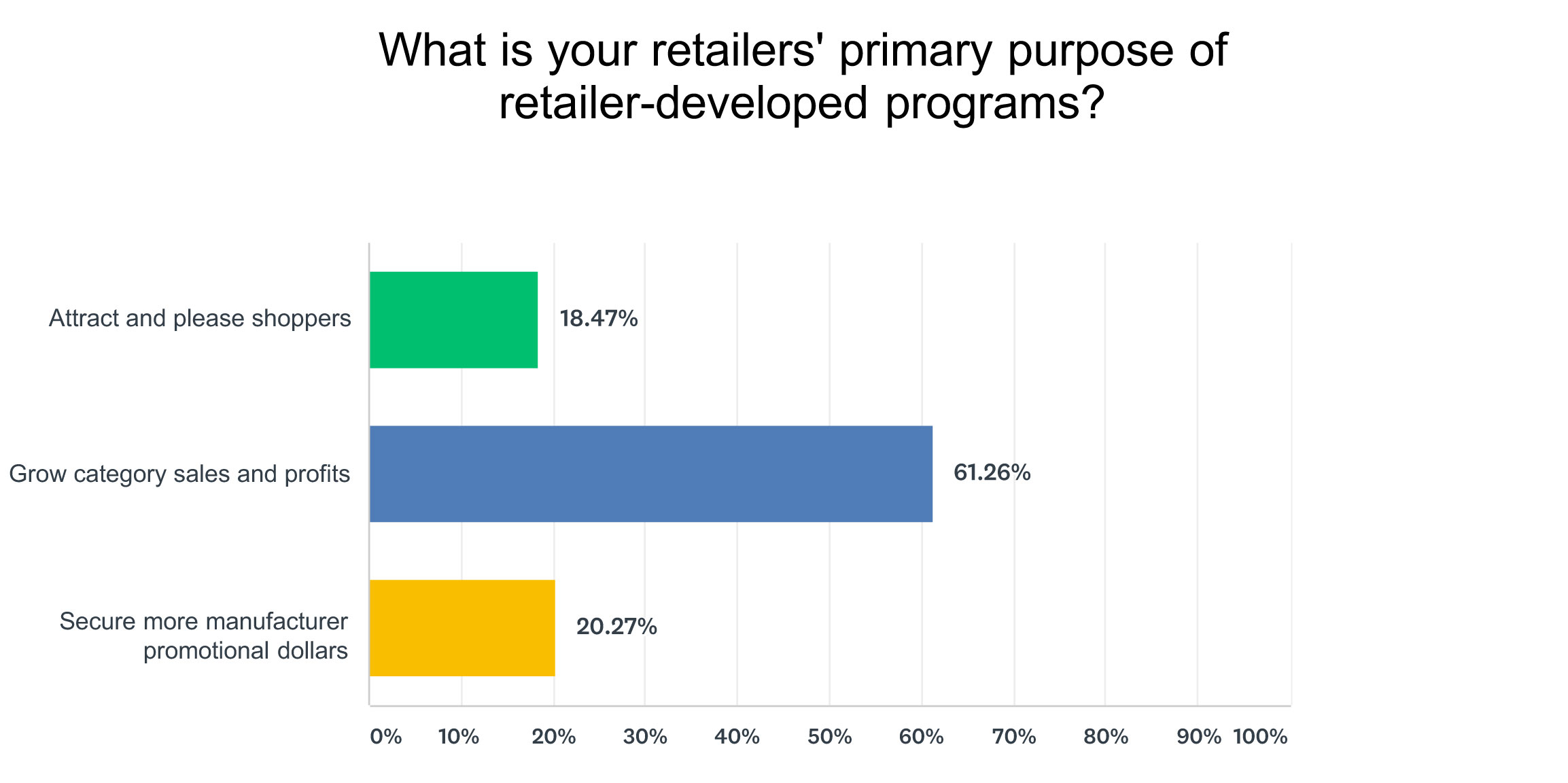

Sixty-two percent said that Shopper initiatives are typically executed through the retailer’s merchandising group, not its marketing group. Sixty-two percent also said that the primary purpose of Shopper initiatives was to grow the retailer’s sales and profits, not to please and attract shoppers. Slightly less than half (49%) were investing in Shopper research. Key metrics of success were: short-term ROI (68%); sales lift (59%); and incremental volume and margin to the retailer (57%). Longer-term, strategic, marketing-focused measures lagged: brand share (38%); retailer penetration and support (29%); return on retailer relationship (27%).

Based on these results, it appears that, despite broad agreement on best-practice as cross-disciplinary and marketing-focused, sales and merchandising dominates how it is implemented and evaluated. Alysia Ross of Danone NA comments: “While a shopper program may be developed to align with brand strategy, the sales team may choose not to execute it if it doesn’t align with the specific priority for their customer.”

Then in our 2018 survey, for the first time, those who reported organizing Shopper as a function of Sales reported better results than those who organized it as a function of Marketing. We can only speculate on what has changed, but one very real possibility is that more organizations have essentially given up on Shopper as it was originally conceived. Instead, they are reverting to activities that look a lot like 20th-century sales promotion or trade amplification, and consider a short-term bump in sales alone to be evidence enough of success.

Perhaps this is a reaction to the zero-growth environment of consumer packaged goods and corresponding zero-based cutbacks and reductions in budgets and headcounts. Either way, it appears that those who view Shopper as an essential part of an integrated brand and retail strategy are increasingly frustrated and find themselves boxed in and unable to produce the kind of results that Shopper promises, and given the chance, delivers.

It’s important to remember that organizations are not the sum total of their org-chart boxes and dotted lines, but of human beings and a culture. Where there’s a will there’s a way, and some true-blue shopper marketers report that they somehow manage to get budgets and develop initiatives to advance their goals and objectives even in the face of organizations that are not set up to support them.

In other words, while how shopper is organized does matter — after all, it goes directly to the definition of Shopper upon which all else depends — there are ways to get the job done regardless. Ultimately, how the people within the organization operate matters more than the structure of the organization itself, and how they define success. “Regardless of where Shopper sits within the organization,” says Mike Clifford of Kellogg’s, “it’s all in how you look at it and how you measure it.”

UP NEXT

June 19th: Are retailer-led programs a problem?

PREVIOUSLY

June 5th: Can someone please define shopper marketing?