An understanding of why people do what they do, when and where they do it as shoppers, distinguishes Shopper from other kinds of commercial activity. It’s the reason why it’s called “shopper” marketing. Separating shopper insight from consumer insight — which centers on what people think, not what they do — may require some mental gymnastics. It is not a distinction that comes naturally to everyone, or even most, people. It is, however, a critically important difference.

An understanding of why people do what they do, when and where they do it as shoppers, distinguishes Shopper from other kinds of commercial activity. It’s the reason why it’s called “shopper” marketing. Separating shopper insight from consumer insight — which centers on what people think, not what they do — may require some mental gymnastics. It is not a distinction that comes naturally to everyone, or even most, people. It is, however, a critically important difference.

Some insist that the difference between a consumer and a shopper is purely functional, the idea being that the person who is doing the shopping is not necessarily the same as the person who is consuming what is purchased. It’s a fair point — moms probably aren’t wearing the diapers they are buying for their babies and dads hopefully are not eating the food they buy for their cats. That’s not the most important difference, though, and really doesn’t qualify as an insight. Who is buying what for whom is a quite obvious, fact-based observation about what people do, and is devoid of any analysis of why they do it, which is where insights take flight.

Shopper insights is largely based on behavioral economics, which is all about how people think about choices and why they arrive at the decisions they make. It’s a fascinating and complex field that’s premised on the notion that most of the time people make decisions quickly, based on what feels right emotionally, versus what would make sense rationally.

Traditional economics assumes that people think like economists, and take the time to calculate an objective analysis of which decision is in their best financial interest. Behavioral economics holds that most people think like people, not economists, and make snap judgements that feel good but are not necessarily in their own best interest. Either we don’t have the time or the energy to think things through, so we default to whatever choice is easiest of just feels right. The propensity to make quick decisions is a survival instinct, basically.

Behavioral economics describes perfectly how most of us approach shopping — certainly grocery shopping and many other kinds of shopping, too. It is a completely different frame of mind than the one we’re in when we’re simply thinking about a brand because we are in buying mode and other factors, most prominently the stress of time and money, weigh in.

Some in Shopper frame such behavior as a “need states” and see the role of shopper as fulfilling that need, as quickly and easily as possible, in the moment. Other take it a step further, setting a more ambitious goal of helping shoppers become a better version of themselves. “It’s going beyond need states,” Barry Roberts says. “It’s going to the want states, which are more emotional. How can we truly deliver on what they want? What are they going to want tomorrow? How can we truly delight them?”

Either way, it’s a big challenge, but it’s one that shopper is tailor-made to meet by making it as easy as possible for people to find and buy whatever it is they are seeking, or better yet discover, while they are shopping. Walmart’s Matt Parry suggests that the benefits of shopper insights is something everyone throughout the organization can understand. “What everyone will listen to is what the shopper is doing and how it helps their business,” he says.

Failure to cater to this primal shopper need may be the single-most important reason why so much shopping is moving online. Shopping in stores can be a colossal waste of time, and once people decide they can get the same thing done faster (and maybe even cheaper) online, that’s what they’re going to do. What should be maximized is the opportunity for discovery that retail stores are so well-equipped to provide. “The moment the customer chooses is more than a place to manage assortment,” says Matt Parry. “It’s a marketing medium.”

Changes in shopper behavior is an existential threat to many brands, once retailers conclude that certain brands stand in the way of an efficient and effective shopping experience and have not earned a place on their shelves. Slotting allowances can’t buy relevance, and brands that are not part of the solution in stores quickly become part of the problem. Such brands likely will find themselves banished to the outskirts of cyberspace, if they continue to exist at all. That’s a troubling prognosis, but the specter of irrelevance is a prospect that must be faced.

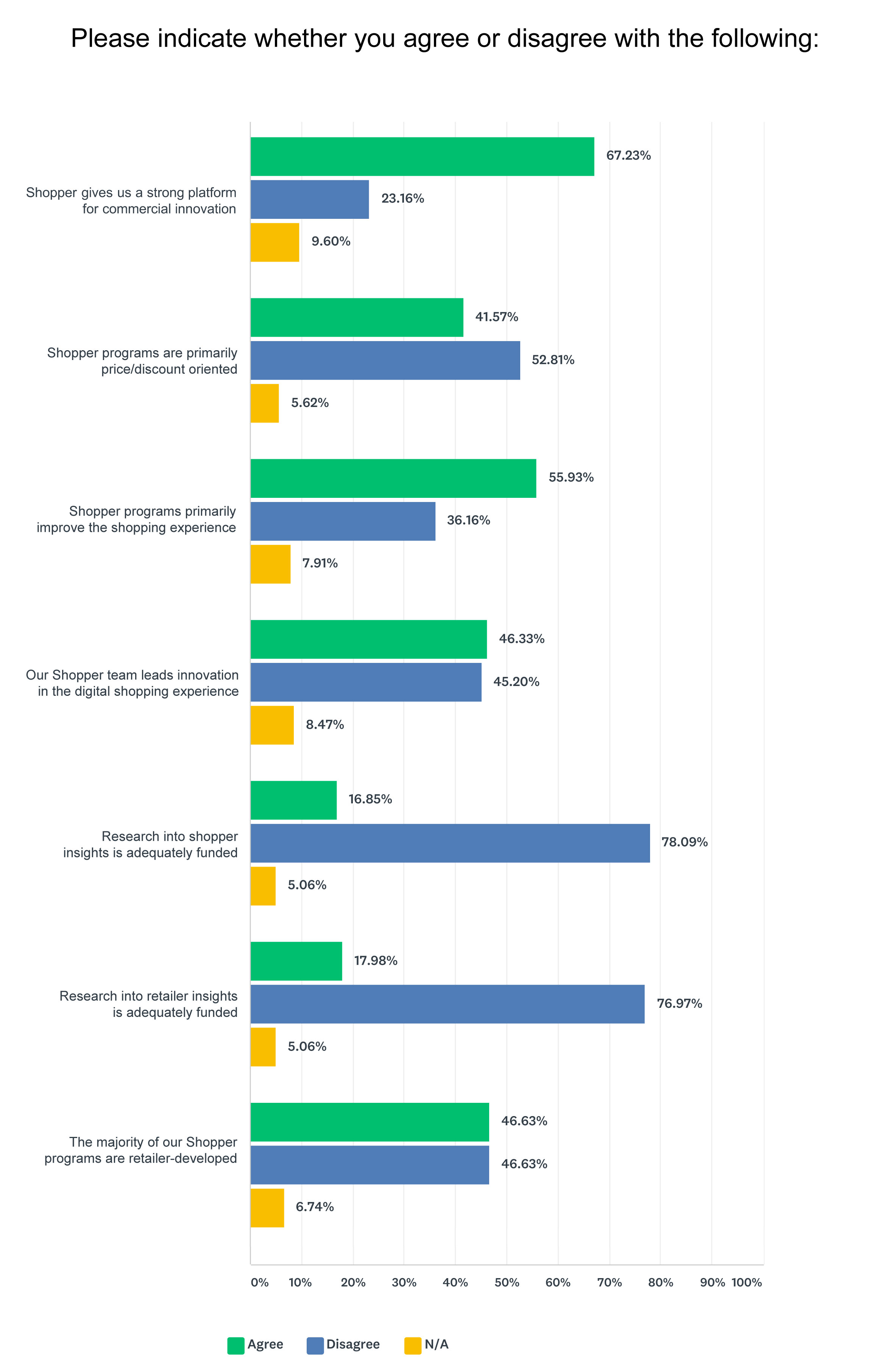

Avoiding such a fate depends on making a robust investment in shopper insights, which, according to our research, is a rarity in most organizations. “In a world with so much data at our fingertips, we lack in general an understanding of shopping behavior,” Tammy Brumfield observes. Most organizations are not investing in shopper insights in any meaningful way, or even at all. The perception persists that consumer insight is all that is needed, but based on the above it should be clear that this is not true. Data points are plentiful, but it is critical to understand the attitudes, beliefs and barriers to purchase.

Ironically, the lack of funding may be a problem caused by Shopper’s alignment with, and control by, the marketing department, which is all about the consumer. As noted, it can be a real leap to internalize the difference between a shopper and a consumer insight, and why this distinction matters. We don’t fund what we don’t understand.

The bottom line is that if you don’t understand your consumer as a shopper, you do not understand your consumer. “We need to sort out when and where shoppers or consumers engage or interact with the brand, what you have to do at each interaction, and how that changes as shopper behavior changes,” says Barry Roberts. This actually is a key opportunity for agencies to step in and fill this void, and provide the leadership that is so often lacking in Shopper.

UP NEXT

July 3rd: Where should digital sit?

PREVIOUSLY

June 5th: Can someone please define shopper marketing?

June 12th: Who cares how shopper is organized?

June 19th: Are retailer-led programs a problem?