One of the guiding tenets of Shopper is that it aligns brand and retailer strategies. Today, this is a given, and in fact it was the foundation of co-marketing, which preceded Shopper. Co-marketing, popularized by Chris Hoyt and others at the early 1990s, advanced the then-novel idea that brands and retailers should sit down at the table with a blank sheet of paper and work out a program that satisfied their mutual, long-term goals and objectives. Previously, brands would go to retailers with a menu of prepared programs from which retailers could pick and choose whatever they liked best. This was generally known as “account-specific marketing.”

One of the guiding tenets of Shopper is that it aligns brand and retailer strategies. Today, this is a given, and in fact it was the foundation of co-marketing, which preceded Shopper. Co-marketing, popularized by Chris Hoyt and others at the early 1990s, advanced the then-novel idea that brands and retailers should sit down at the table with a blank sheet of paper and work out a program that satisfied their mutual, long-term goals and objectives. Previously, brands would go to retailers with a menu of prepared programs from which retailers could pick and choose whatever they liked best. This was generally known as “account-specific marketing.”

Just as co-marketing built on account-specific marketing by aligning brand and retailer goals and objectives, Shopper built on co-marketing by introducing the idea of blending consumer and shopper insights. This took the focus off the relationship between the brand and the retailer, placing it where it truly belongs, on their mutual interest: the consumer (from a brand’s perspective) and the shopper (from the retailer’s perspective).

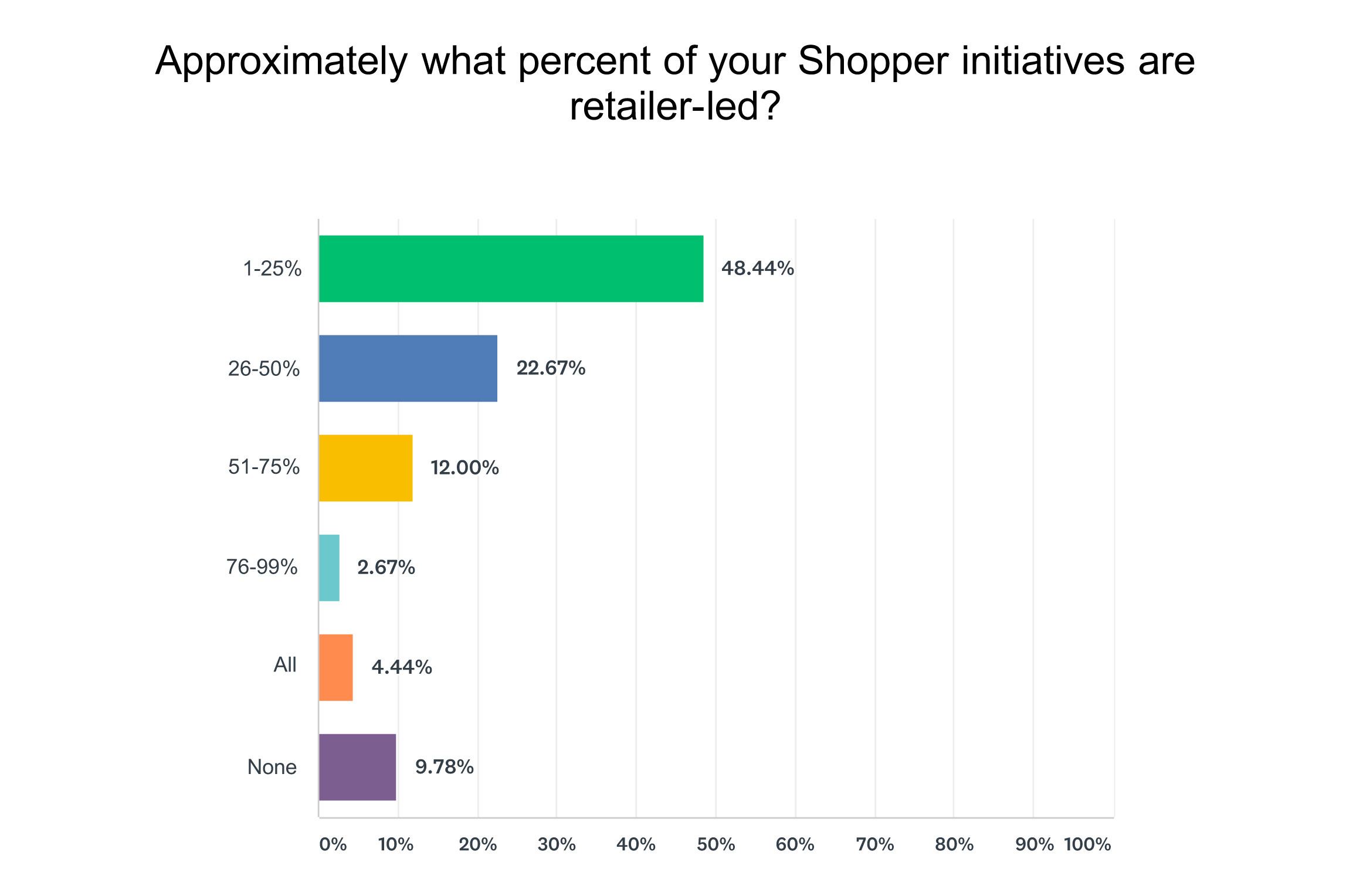

With the rise of retailer power, and retailers as brand-builders in their own right, came the advent of retailer-led programs, which the retailer develops and sells to brand owners. Typically, these programs are linked to a season or a high-impact cultural event and give brands a certain level of visibility through displays and logos in the store and other related marketing activities.

Sometimes programs are sufficiently sophisticated to allow brand owners to enjoy a branding opportunity, but often it simply means that the brand’s logo is slapped on a display, along with the logos of several other brands. If this qualifies as Shopper, let’s at least agree that it is really bad Shopper. The brand and retailer may have a mutual interest, but it’s a tactical one at best, and is not based on any real consumer or shopper insight.

Is this a problem? It might not be if the retailer-led program is about more than just logos. “We’ve been able to participate in retailer-led programs in a way that is focused on visibility for one of our priorities,” says Debbie Zefting, director of shopper strategy and engagement at Barilla USA. “Sometimes you can work with a retailer to have their program work for you as well as work for them.”

In some cases, participation in these retailer-led programs are a prerequisite of any truly strategic Shopper initiative. So, whether it’s bad or good is not always considered; sometimes it’s just part of the cost of doing business.

From a retailer’s perspective, the opportunity to participate in a retailer-led seasonal event can be bigger than brands sometimes realize. “We want to create moments in the store,” says Matt Parry of Walmart. “There are places where brands can play a role by highlighting new products and creating excitement.”

Indeed, often there are more chances to collaborate than meet the eye. A retailer’s opportunity is beyond just the purchase experience to the total experience, and Shopper spans all of the marketing touchpoints across the entire ecosystem from a retailer standpoint.

The danger is, if programs are broadly regarded as Shopper but do nothing to advance the brand strategy, they potentially set it back. “Sometimes retailer events are not Shopper events, they are trade events,” says Mike Clifford of Kellogg’s. “Decisions will need to be made regarding whether or not Shopper should fund them,” he adds. Fuzzy funding can give Shopper a bad name, or at the very least reinforce the wrong impression of its true purpose and potential.

Category management is a related issue, in that a category management-based approach to Shopper is a default position because its primary focus is on sales volume, not consumer engagement or shopping experience. Perhaps the greatest tension between brand and retailer is that the brand’s priority is the brand, while the retailer’s is the category. This is a gulf that Shopper was designed to bridge, but as long as category management is the organizing principle, the brand’s interests are in danger of being subsumed.

So, too, are the shopper’s interests. To the extent shoppers have an emotional connection while shopping, categories are all but irrelevant. In fact, categories, as a construct of brand and retailer operations, not only may have little to do with what a shopper hopes to accomplish in the store, they can even make it harder to find and buy whatever it is they are looking for. This results in wasted time, which is arguably the main reason why so much shopping is moving online — because it is a more efficient way to shop.

Barry Roberts, former head of Shopper at Colgate-Palmolive sees opportunities for brands to tell their story at the shelf. “We can bring to life what shoppers really want as to opposed to just focusing on their need state,” he says, adding: “If you’re clear about what your brand stands for, how you connect to your consumer emotionally, and how that drives conversion, retailers will be highly receptive.”

The most important factor relative to the brand-retailer relationship is that brands take the time first to identify the retailers that are most important to their success. For many brands this is a short list of no more than ten retailers, and for some it is as few as just one. Such focus is essential not only from a strategic standpoint, but as a practical matter also place resources where they will produce the greatest effect. It’s not possible to have meaningful partnerships with more than a relatively small, highly considered set of retailers.

Just as important, brands need to invest in understanding the goals and objectives of their retail partners in detail, which, along with understanding shoppers, is a founding principle of Shopper. The brand must know exactly what a retailer can and cannot — or will and will not — allow in its stores.

Dina Keenan, chief marketing officer of New Seasons Markets comments: “Brands need to take the time to understand the unique complexities and challenges of retailers from an operational standpoint, and what it takes to align goals and objectives to meet the retailer’s needs.” The most brilliant strategy from the brand’s perspective will get exactly nowhere if it is not aligned with the realities of the retailer’s policies, practices, rules and culture.

The opportunity, says Tammy Brumfield, is for the taking: “Retailers are perplexed why there isn’t more partnership around data for truly understanding shopping behavior and then building mutual strategies as a result of that understanding,” she comments. “They want someone to step up to the plate.”

UP NEXT

June 26th: Is there any such thing as a shopper insight?

PREVIOUSLY

June 5th: Can someone please define shopper marketing?

June 12th: Who cares how shopper is organized?